Ph.D. Candidate Hongpeng Wang Studies the Big Impact of a Small World

Industry-leading tools help reveal the structure and function of proteins.

Hongpeng Wang has an almost reverent appreciation for the power of proteins.

“All of your cell function is done by proteins,” he said. “You can think and your fingers can move because some protein enzymes work together to give you energy and make that happen.”

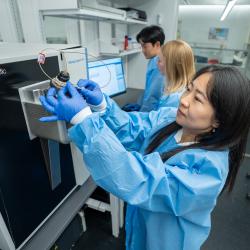

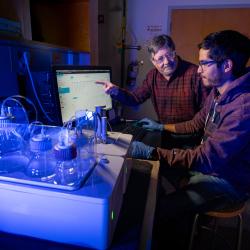

Wang is a biochemistry Ph.D. candidate studying the structure of proteins and how their form relates to their function. He works in the lab of University of Maryland Chemistry and Biochemistry Associate Professor Nicole LaRonde, and he collaborates with Edvin Pozharskiy, an assistant research professor at the Institute for Bioscience and Biotechnology Research (IBBR).

To understand and characterize the structure of molecules, Wang needs some of the most advanced tools technology has to offer. Specifically, he needs a cryo-electron microscope (cryo-EM), which allows him to freeze his tiny subjects and keep them cold while bombarding them with electrons.

Until last year, that meant Wang had to take his samples to facilities in Texas and San Francisco. But now, he can examine the structure of molecules at IBBR’s new cryo-EM facility, just 30 minutes from campus.

IBBR is a unique collaboration between the University of Maryland, College Park; the University of Maryland, Baltimore; and the National Institute of Standards and Technology, which brings together scientists and resources from academia, industry and government to advance biotechnology research and development.

Pozharskiy has been teaching Wang to work with cryo-EM, and together with LaRonde, they have characterized the structure of an enzyme called protein arginine methyltransferase. They found that the enzyme changes conformation when bound to a ligand, a small molecule that helps the enzyme do its job.

Wang is now focusing on understanding how the enzyme uses different adapter proteins to modify the amino acid arginine in other proteins. One of the adapter proteins he is studying is involved in the development of ribosomes, which are the machinery responsible for making proteins inside living cells.

“Ribosomes are important to cancer, because cancer cells need a lot of protein to grow at faster rates than normal cells,” Wang said. “Understanding the mechanism of interaction between arginine methyltransferase and the adaptor proteins could provide a potential target for cancer therapy.”

Wang prepares his samples for cryo-EM by purifying a protein solution and then applying it to a thin grid. He then flash-freezes the solution in a process that creates vitreous ice. With the proteins frozen but intact, the electron microscope bombards them with an electron beam and generates an image, much the way a photograph creates an image based on how an object scatters light. By processing multiple images through a computer, Wang is able to reconstruct the 3D configuration of molecules in his samples.

Wang’s daily routine of preparing proteins and guiding electron beams to capture their miniscule structures is a long way from his childhood on the plains of Henan province, China. He grew up in a small village where his parents eked out a living growing corn, wheat and sometimes vegetables on a half-acre plot of land. Although they only went to middle school, Wang’s parents instilled in him from a very early age the importance of going to college.

“My parents always told me, ‘You should make money based on your knowledge, not your labor.’ And they saved their money and supported me to go to college,” Wang said.

Wang earned his B.S. in biotechnology from Henan Agricultural University in the regional city of Zhengzhou. He then moved to Shanghai for graduate school and earned his M.S. in biology from Shanghai Jiao Tong University. Wang’s educational journey from a rural village to one of the world’s most populous cities broadened his worldview while his intellectual pursuits grew increasingly focused on smaller and smaller things. Eventually, he found his passion studying biology from a molecular perspective.

“In middle school, I loved biology,” Wang said. “I loved learning about animals and plants, how they are composed and classified. In college, I learned about the role of proteins in cell function, and so I became interested in molecular biology.”

Wang was enthralled to find there were answers to questions most people never think to ask, like why do people grow?

“You know people grow, but you don’t know why,” he said. “And I thought it was so cool when I learned that people grow because their cells synthesize protein and those proteins have the functions to help the cells divide.”

As an undergraduate, Wang worked in a lab, and one day, he asked the scientists what the proteins they were studying looked like, and how they knew why they functioned the way they did.

“They didn’t know,” he said. “And I just really wanted to know. So, I went to do my master’s degree in structural biology. It was a way of seeing the protein, of knowing why this protein does this function.”

Now that he is at Maryland working with the advanced technology available through IBBR, Wang has the knowledge and the tools he needs to answer those questions for himself. Wang plans to complete his Ph.D. in 2021. He hopes to stay in the area a little while longer for a postdoctoral fellowship, where he can continue to pursue his fascination with the power of proteins.