For Theoretical Chemist Pratyush Tiwary, It’s All About Perspective

Pratyush Tiwary learned about balance on the banks of the Ganges river. He was a college student attending the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology in the city of Varanasi. The oldest city in India, Varanasi is steeped in mysticism and ancient Hindu traditions, and it draws pilgrims seeking spiritual awakening from around the world.

“It was just the balance of doing computer programming all day, taking all these heavy classes and then going on my bicycle to sit on the banks of the Ganges,” said Tiwary, an assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of Maryland who has a joint appointment in the Institute for Physical Science and Technology (IPST). “It made a huge impact on me, sipping tea with people from all over the world and on a daily basis seeing people having these very spiritual ceremonies—bodies being cremated across the river in these very ancient traditions. It took me out of the very competitive intense environment of academia and reminded me that there is something so much more to life than just working for money.”

Before moving to Varanasi, Tiwary spent his first year of college studying math at the Indian Statistical Institute in Bengaluru. Inspired by the heroic biography of the Indian mathematical genius Srinivasa Ramanujan, Tiwary had worked hard to get into the prestigious and highly competitive school. But he quickly ran up against his personal need for tangible results. He preferred the application of math to the study of pure mathematics.

“I realized that being inspired by a mathematician is not the same as doing math itself,” Tiwary said. “I found pure mathematics very dry, and I struggled with it. If I had stayed, I would have been a mediocre mathematician.”

Fortunately, for Tiwary, he did not stay. He changed course, turning to the study of metallurgical engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology. There, everything clicked. The program turned out to be the perfect intersection of his interests in physics, math and chemistry, and by the time he graduated with his Bachelor of Technology degree, he had published three papers in international journals as the first author.

Now, Tiwary performs theoretical chemistry and statistical mechanics research, and he has authored or co-authored nearly 50 articles in scientific journals. Using artificial intelligence and the laws of thermodynamics, he simulates the behavior of molecules and atoms in complex systems. This kind of work is important for advancing medicine and materials science and it can help answer questions, such as when molecules in a given medicine stop interacting with cells in the body.

In a paper published in the journal Nature Communications in late 2020, Tiwary and his team developed a method for predicting the behavior of protein molecules using machine learning tools, like the kind Google uses to autofill words as someone types. His team’s method involved creating an abstract language that describes the multiple shapes a protein molecule can take and how and when it transitions from one shape to another. Because the shape of a protein molecule often determines its function, this work can provide insight into everything from how a protein works to the causes of disease and the best way to design targeted drug therapies.

In February 2021, Tiwary received a Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) award from the National Science Foundation (NSF) that provides five years of funding for his proposal “Learning to Learn—Artificial Intelligence Augmented Chemistry for Molecular Simulations and Beyond.” The $650,000 award will help Tiwary in his quest to improve molecular dynamic simulations with artificial intelligence while also advancing scientific understanding of how artificial intelligence works.

For Tiwary, there is no better place to dive deeply into the study of molecular dynamics and statistical mechanics than UMD. After earning his M.S. and Ph.D. in materials science from the California Institute of Technology, he completed postdoctoral fellowships at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zürich and Columbia University and then came to Maryland in 2017.

“There is no place in the world which compares to Maryland in the quality of theoretical chemistry and statistical mechanics,” Tiwary said. “This is the place to do statistical mechanics, and it’s still intimidating to go to lunch with some of my colleagues here and talk about thermodynamics. I mean, these are people whose names are scattered through all my books from grad school.”

High-quality research is what drew Tiwary to UMD, but he said he was happy to find a supportive culture that aligns with his sense of balance in life. Academia can be stressful and competitive, and Tiwary actively seeks ways to bring perspective to his work both in the lab and the classroom.

On one corner of the whiteboard that hangs on his office wall—amidst the calculations and scribbles from the day’s brainstorming—Tiwary keeps a running list of all his grant proposals, with columns for the ones that received funding and those that did not. It’s a reminder to himself and everyone who walks into his office that in science, for every success, there are many more failures.

“It’s very easy to highlight our achievements and forget about all the times we failed in order to get there, especially in the very beginning when you don’t know how to write good proposals,” he said. “I think it is important for us to be open about it, and for students to see and understand that the acceptance rate is very low, and you may have to apply 10 times to get that first grant.”

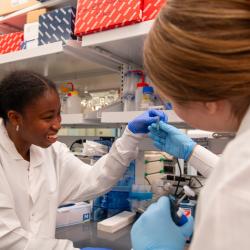

Helping students succeed and feel comfortable with their progress is important to Tiwary, who is currently mentoring seven Ph.D. students and five undergraduates. He likes to meet with each student at least once a week, but COVID-19 has made it difficult for him to feel connected with them.

“I really miss meeting my students in person,” he said. “It’s hard to gauge how they are feeling and how they are doing in general.”

Connecting on a personal level through a remote learning format is even harder for large classes like the 100-student CHEM 481: Physical Chemistry I course he taught last fall. But Tiwary found a way to bring a sense of warmth and fun by setting up a channel dedicated to posting pictures of his dog, Pakora, on the messaging platform Slack.

“I would just post pictures of Pakora, and the students would post pictures of their dogs, and occasionally cats and bunnies, and that just made the whole experience so much more human,” he said. “It makes me someone other than just the person who expects mastery over thermodynamics. I’m a real person. And so many students wrote in the feedback that the class gave them a reason to wake up at 9:00 a.m. on a Monday.”

Months later, his students still reach out on that channel to check on him and Pakora. Tiwary’s enthusiasm for mentoring extends beyond his students to the broader community, where he shares his passion for using computer science to tackle all sorts of physical science questions.

This summer, he will run computer literacy workshops for science students at Prince George’s Community College and Bowie State University, as well as for current and future science teachers through UMD’s Terrapin Teachers program. The goal of the workshops, which are being funded by his NSF CAREER award, is to give participants the awareness and coding skills needed to tackle the interdisciplinary science challenges facing biologists, physicists, chemists and others today. Students who show an interest and aptitude for coding through the workshops will have opportunities to get involved in research projects with UMD faculty members.

Between research, teaching and outreach, Tiwary carries a pretty heavy workload. It helps that he can bounce ideas off his wife, Megan Newcombe, who understands the challenges as an assistant professor herself in UMD’s Department of Geology. However, since the days when they first met as graduate students at Caltech, they’ve learned not to talk about thermodynamics.

“Most of our arguments are around thermodynamics,” he said with a smile, “because that’s a common theme for our fields. She studies volcanoes, how they form, how they erupt and things like that. It’s too close. We both think we are right, so we have stopped talking about that. Although we are working on a joint grant proposal for the future.”

Of course, there are times when Tiwary needs to unplug completely from work. For that, he runs—six days a week, up to 60 miles. The routine has given his life some structure during the pandemic, but his running habit began when he was in graduate school. It was a way to stay fit for mountaineering, which he developed a passion for while living in California. He became the president of the Caltech Alpine Club and climbed mountains in Washington State and Mexico. He even went back to India, where he climbed to 21,000 feet in the Ladakh Himalayas.

After a few harrowing climbing accidents requiring helicopter rescue, Tiwary shifted his focus to running, which is not only safer, but can be combined with Zoom meetings if needed. Now, he runs the trails around campus and into Washington, D.C. Since moving to Maryland in 2017, Tiwary has logged around 7,000 miles and finished three marathons. His goal is to run a marathon in three hours before earning tenure. Last fall, he ran one in 3 hours, 40 minutes.

That’s a major improvement over his first marathon—a six-hour affair when he was 23 years old. And it’s a much different goal than the one he set when he first moved to Maryland.

“When I became an assistant professor, I thought of running as a kind of hedge against a really stressful career,” he said. “I thought if I run a lot and the science career doesn’t go well, at least I will be fit at the end of it.”

It seems like both the running and the science are working out quite well for Tiwary.

Written by Kimbra Cutlip